Originally featured in Student Life

When Lindsay Gassman was a second year student at Washington University in the fall of 2018, she noticed that few of her peers were thinking ahead about voting in the upcoming midterm elections. The midterms generated some energy and enthusiasm on campus, she recalled, but the elections were not at the forefront of the student body consciousness. This year, attitudes surrounding the election have shifted.

Even though there are fewer students on campus, the change is still noticeable. Now the Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement’s Voter Engagement Fellow, Gassman has been getting emails since the summer from freshmen who are eager to register to vote.

“This year, people seem to be much more proactive about voting,” Gassman said. “It seems like there are a lot more students taking proactive steps, getting informed and getting involved.”

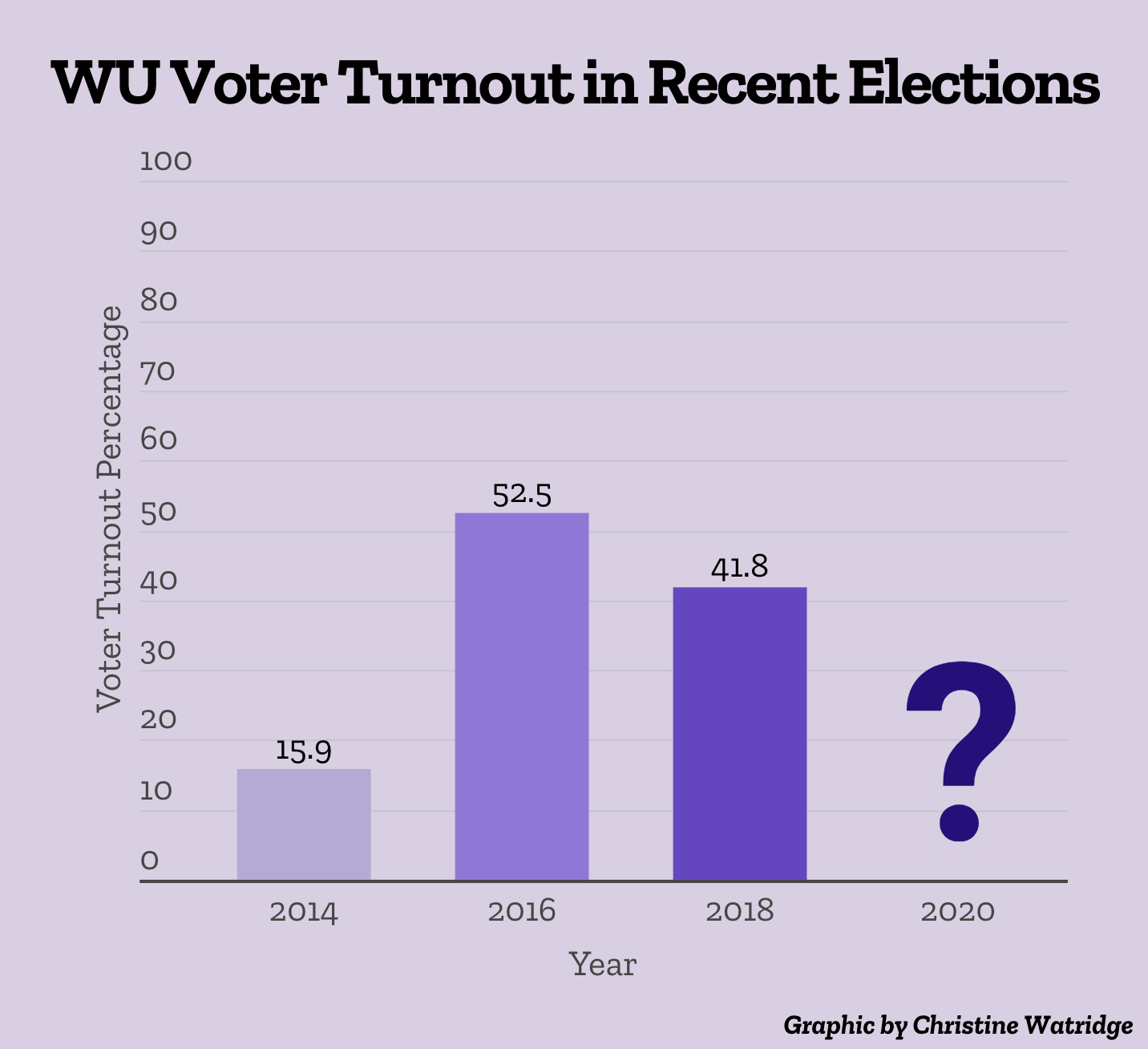

That planning and engagement bodes well for voter turnout on campus. Just 52.5% of eligible students voted in 2016 and 41.8% in 2018, but this year, WashU Votes, Gephardt’s voter engagement partner, has set a goal of having 62.5% of eligible students vote. As students head to the polls today, there is optimism that student voter turnout will increase from past years to meet that goal.

“I think we can definitely hit that,” sophomore Otto Brown, the outreach chair for WashU Votes, said. “There’s a lot of energy around voter engagement, turnout and registration.”

According to Brown, from August to Oct. 14, 2,536 Washington University students registered to vote, leaving the University’s total behind only Stanford University and the University of Chicago. Brown said that 33.4% of the University’s undergraduate population used the website TurboVote to register to vote between those dates, the second highest percentage in the country. “That’s huge, so we were pretty proud of those numbers,” he said.

Registering students to vote required a multi-faceted approach. The WashU Votes team spent much of the summer transitioning its traditional, in-person model of registering voters through tabling events in spaces like the Bear’s Den and the Danforth University Center to an online format. The organization also launched an Instagram account and has developed partnerships with student groups. “We’ve put a lot of effort into making sure that everyone who has the opportunity to vote is able to make that choice to vote,” Brown said.

In addition to communicating the specifics about how to vote, there have been efforts over the last few years to build a more celebratory environment around the act of voting itself. “Voter mobilization studies have demonstrated that activities like food and music and fun surrounding turnout actually boosts turnout way more than something like putting up a sign on Mudd Field,” Betsy Sinclair, a professor of political science who studies the role of social influence on democratic practices, said.

This year, however, since the pandemic has pushed so much voter registration and mobilization online, there have been other factors encouraging students to vote.

As with voters across the country, issues like racial justice and the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic are motivating students to vote.

“I think having these two really strong examples of policies throughout 2020 has really mobilized a lot of students to realize ‘Oh, I need to be taking action. I need to be investing in my community, I need to be protesting, I need to be donating to mutual aid funds. And also, I need to be voting,” Gassman said. “A lot of students are looking at voting as one response to the events of this year, definitely not the only response.”

It has been hard to avoid conversations about voting this fall. “People are telling [students] that this is the most important election for their generation,” Sinclair said. That messaging can have an impact on turnout, she said, because social pressure encourages people to act the way they see others behaving. “There seem to be people thinking about what people like them are doing and participating because a tremendous amount of the calculus of voting is based upon our norms,” she said.

Especially given the increased interest in the election, Missouri state law has complicated students’ efforts to vote this fall. While the state legislature created universal mail-in voting this year, mail-in voting and most absentee voting methods both require a notary’s signature. As a result, lists of places to get ballots notarized have been an important feature of voter engagement on campus, joining explanations of the different ways to vote on social media and in informational emails.

Missouri’s March 10 presidential primary served as a trial run for the fall general election, Gassman said. Since the primary took place while most students were away for spring break, Gephardt and other campus partners worked to provide opportunities for students to notarize their absentee ballots on campus.

“That was foreshadowing what would return later this year as far as lots more students choosing to vote by mail and vote absentee,” Gassman said. Data suggest that the University’s work is paying off. As of Oct. 26, Gephardt had helped students notarize 258 ballots, over 100 more than it had before the March election. “It’s clear that a lot of students are seeking out these resources,” Gassman said.

“Students are seeing the options that they have to vote and are going ahead and voting early and voting by mail,” she added, noting however, that there were still many students who plan to vote in person on election day.

The increase in voter turnout over the last few years aligns with national trends, with the University’s turnout rates typically slightly higher than the national average. A 2019 report from the Institute for Democracy & Higher Education (IDHE) at Tufts University found that the national student voting rate was 40.3% in 2018, up from an average of 19.3% in 2014.

When Nancy Thomas, who leads the IDHE’s National Study of Learning, Voting and Engagement, first sent colleges and universities data about their students’ voter turnout in 2014, she was met with a stunned response. Administrators could not believe how few students were voting. School leaders called her office to ask if their single-digit voting rates were data errors or typos. They were not.

“The data were a real wake-up call for campuses,” Thomas said. “I don’t think, however, that campuses fully opened their eyes until 2016,” Thomas said.

After Donald Trump’s victory took much of the country by surprise, colleges found their voting reports and decided that it was time for a change: “They took a look at [the reports] and said ‘We really need to step it up,’” Thomas explained. Since then, colleges and universities have become much more engaged as institutions, she said.

Rising turnout rates over the last few years have resulted from a confluence of three factors, Thomas said: many students have seen elections as referenda on the Trump administration; many schools, like Wash. U., have started to address the stark data they received in the early 2010s; and there has been increased student activism more generally.

“Those were the three things that were in play in 2018 and if you think about it, all three are in play in 2020,” Thomas said. “For that reason, before the pandemic, I was telling college presidents not to worry about 2020 and that they should be focusing on 2022, setting up systems and structures that would be embedded and institutionalized so that the next midterm, they wouldn’t be disappointed.”

The pandemic sidetracked those plans. Thomas cautioned against using data from this year’s voter turnout as an indication of any trends. Since there have been so many changes to voting laws—including numerous legal challenges that are still pending—and the pandemic provides unique challenges, she said it was too soon to tell whether researchers would be able to adequately put this year’s numbers in context.

Challenges like ballot notarization or fear of the contracting COVID-19 at the polls explain why some students will not vote this fall. But even some of the University’s most politically-engaged and well-informed students will not be voting in the presidential election this fall.

In addition to costs of voting like transportation to a polling place or lost work hours, the candidates themselves matter. “A lot of students just feel completely disenchanted with the political process and genuinely see both current candidates as supervillains,” Sinclair said.

Senior Sabreen Abdullah is one of those students. She plans to vote in local elections, but not for any presidential candidate, since she feels as if neither candidate would provide substantive systemic change. “For the people I’ve talked to who aren’t voting, it’s not about the process of voting,” she said. “They’ve always felt excluded before and the candidates are now trying to get them to come out and vote, but they’re going to turn around and make policies that will hurt the people they’re asking to vote.”

Abdullah said that she likely would have encouraged her entire family to vote if a candidate like Bernie Sanders was on the ticket. “I would definitely vote for someone I thought could bring actual change.”

Gassman noted that disenchantment with the political process was something she has encountered with many students this year. She recognized the power of direct action, but argued that voting is a crucial aspect of supporting your community. “Although the concerns about the system are valid in many circumstances, there is still value in voting as the next step forward so that there can be people in office who are listening to the demands of the people who work outside of the electoral system,” she said.

For those students who choose to vote in-person today, the on-campus polling place will look different than it did for the 2018 midterms. Since only 15.9% of students voted in the 2014 midterms, the St. Louis County Board of Elections allocated only two poll pads—the devices used to check voters into the polls—to the Athletic Complex voting site in 2018. Coupled with other factors like a limited number of staffers, that allocation contributed to waits of up to three or four hours for some students.

This year, there will be four poll pads at the Athletic Complex voting site. In addition, St. Louis County residents are now able to vote at any one of more than 200 polling places. Gassman said there will also be a virtual queuing system in place at the Athletic Complex in order to reduce voter wait times. “You can think of it like when you show up to a restaurant that’s full and you get a text to come back,” Gassman explained. “People will be able to wait anywhere on campus and then return to the polling place when they get a text to wait in line in-person,” she said. Still, voters must be in line in-person by the 7 p.m. close of the polls in order to cast their ballot.

Despite the inevitable stressors of the days to come, Sinclair finished with a note of hope for the future. She emphasized the role of habit in voting, as studies have shown that after someone votes once, they are likelier to do it again the next time around. “If we do see this increased turnout from younger voters this election cycle,” Sinclair said. “We’re going to hear this generation’s voice for the rest of your lives.”